In A Mind Forever Voyaging: A History of Storytelling in Video Games, Dylan Holmes references the 1995 text adventure of the same name. He describes it as “one of the first games to place an overt emphasis on narrative exploration and showing rather than telling.” That game, and by extension Holmes’ history, refers in turn to a passage in The Prelude, Wordsworth’s long poem, where the “mind” belongs to a Newton of the poet’s imagination. I only know this bit about Wordsworth because the book’s epigraph makes the connection, citing the relevant lines of iambic pentameter; and as for the Steve Meretzky text adventure, I would never have heard of it but for the note in the book’s appendices. Recounting it like this may seem pedantic, telling rather than showing, but if, like me, you enjoy learning new things right from the title of a book, digging into the layers of meaning behind a single resonant phrase, A Mind Forever Voyaging will make for an illuminating read.

Through this play of allusions to literature and science, Holmes’ analysis of video game narratives gets underway. It opens with a short preface, asking “what do we do with interactivity? How do games make choice–not just the individual choices, but the act of choosing, of influencing a narrative–interesting?” Each chapter that follows takes on a single game, exploring how its affordances of player choice further our experience of the story and expand our sense of the possibilities of storytelling.

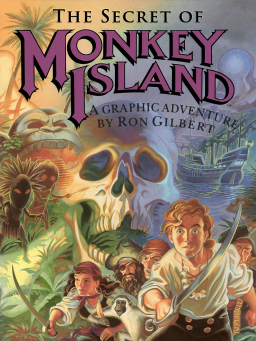

The first chapter, on The Secret of Monkey Island, is the only one placed out of chronological order. Serving as the author’s point of coming to consciousness with respect to games, the way so many game protagonists wake from sleep at the start of their adventures, the Monkey Island chapter sets the trajectory of Holmes’ tastes. It also previews some of the book’s main concerns and reveals certain assumptions behind the argument. Here and throughout the book, Holmes strikes a balance between memoir, summary, and explication. We get enough of a sense of why he cares about the games he’s chosen from a personal standpoint, and enough of a description of the games’ most important features to then dig into some of their particular storytelling qualities. In the case of Monkey Island, this entails descriptions of his first impressions of the game before he could even read, of the game’s comedic dialogue, and a critique of its use of pacifism and (the illusion of) player choice. In this way, Holmes begins to engage with questions of genre, narrative, cinematic storytelling, and other themes that will run through the book, without either wading into overly academic territory or pretending to be anything but a subjective guide.

His gaming palette is much broader than my own. The succeeding chapters circle back to touch on Planetfall, Ultima IV, and System Shock, before reaching the original release of Final Fantasy VII, the only game in the book which I’ve played to any significant extent. The inclusion of text adventures, PC games, and western RPGs ranging over so many aesthetic gradations, from the goofy to the pretentious, greatly expanded my understanding of how far video game storytelling had already come by the time I first sat down to play Mario, Zelda, and 90’s JRPGs like EarthBound and Xenogears.

Thus, I value and appreciate the new insights this book holds for me and, I have to imagine, for many people who might have had a similarly narrow exposure to games (whether that might be limited to Sega consoles, 3D platformers, fishing sims, or something else). This also means that I’m not really in a position to assess Holmes’ critical eye, lacking firsthand knowledge of Half-Life, Shenmue, or Deus Ex (beyond the first mission or two), to say nothing of the more recherché likes of Façade, Dear Esther, and Heavy Rain. Based on what I’ve read, I’m grateful to Holmes for introducing me to all these titles and sparing me the significant investment of time and money necessary for playing them. His work of distilling out their essential contributions to an art form, helping me to see it in new ways, seems very much a labor of love. To extrapolate from the discussion of FFVII, which is excellent and concise, I’m inclined to trust his judgment.

Ultimately, AMFV builds up a coherent history of the medium circa 2012. Without, as far as I can tell, discovering anything earth-shattering about any particular game under discussion, Holmes’ approach of bringing these games into conversation with one another makes a strong case for their development of new and unique ways of telling a story with the participation of players. Besides the games so far mentioned, there are separate chapters on both Metal Gear Solid and MGS2, which strikes me as a somewhat strange choice. It makes sense, though, given Holmes’ interest in the cinematic qualities of games and in the ways in which games have increasingly acquired self-awareness of their potential to subvert player expectations. Still, I couldn’t help wishing these chapters had been combined to make more room for discussions of games that didn’t make it into the book. The single “intertitle” chapter similarly seemed like it could just as well have been integrated into a spotlight on another game. He appends a shortlist of such games he would have liked to include, dedicating a paragraph rather than a chapter to noting what innovations each brings to the development of storytelling in games: Myst, Grim Fandango, and Planescape: Torment, to name a few, along with console games like Legend of Mana and Silent Hill 2.

While there are plenty of reviews, analyses, and postmortems out there of individual games, series, and even genres, it’s not so common to find a welcoming, well-written book for the general reader that consolidates so much about whole generations of the medium. The only other one I’ve encountered, which was published around the same time and which Holmes cites approvingly, is Tristan Donovan’s Replay: The History of Video Games. But if my recommendation of A Mind Forever Voyaging isn’t sufficient, I hope that Gabrielle Zevin’s seal of approval convinces more people to pick it up, as it’s one of the handful of books she mentions in her acknowledgments of her brilliant novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow.

Rounding out the book, there is a conclusion in which Holmes sums up his argument: “What makes video games so exciting is not that they tell great stories, but that they tell stories differently.” Through the use of player choice, cinematic cutscenes, a whole panoply of gameplay yielding real-time interaction, plus more literary tools like flashbacks, playful self-reference, and intertextuality, video games continually experiment with the art of storytelling. In the relatively short space of 240 pages, hardly “forever,” Holmes manages to take us on a fantastic voyage showing how these disparate elements combine in the worlds revealed by video games.

![]()

PIXEL PERFECT

Recommended

![]()

Wesley Schantz coordinates the Video Game Academy, writes about books and video games, and teaches in Spokane, WA.

![]()